Interview with Ivana Momčilović, The Playwright of Holes

One of the last guided tours through the exhibition The Nineties: A Glossary of Migrations, with its authors will be organized on Saturday, February 22, at 1 p.m. at the Museum of Yugoslavia (the May 25 Museum facility). Authors and curators, Simona Ognjanović and Ana Panić, will be joined by the writer of the play Holes or When We Were Non-Aligned, Ivana Momčilović, as well as some of the actors from the play, the so called Invisibles – refugees from war-torn areas during the 1990s, the displaced, the former military personnel, Roma, who played themselves in the mentioned piece.

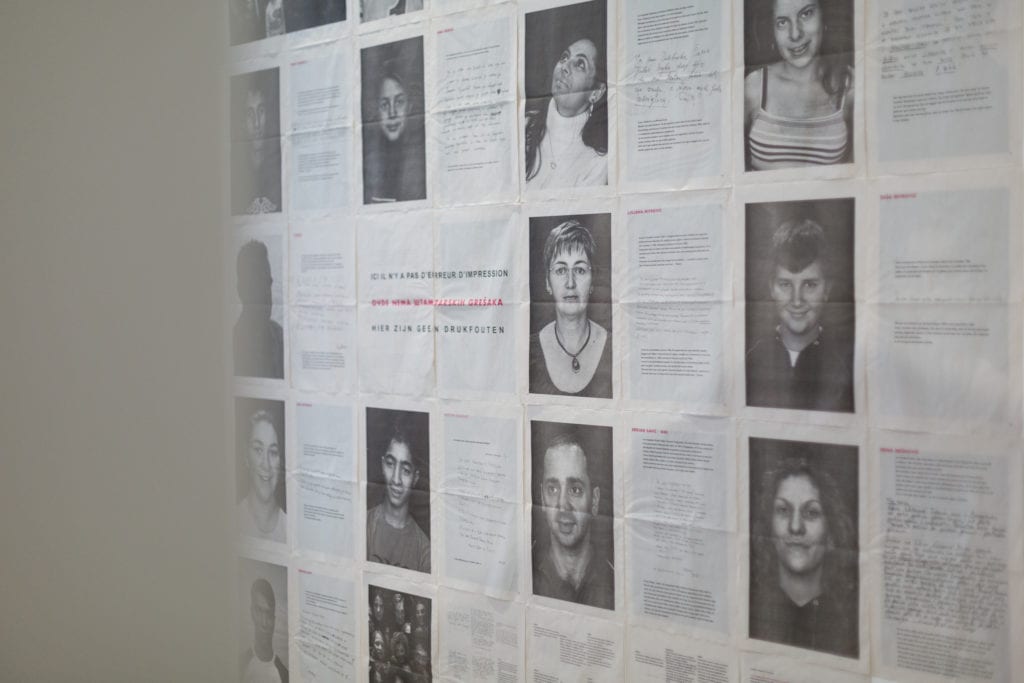

The play Holes or When We Were Not Aligned, written by Ivana Momčilović and directed by Lorent Wanson, was created in co-production of the National Theatre in Belgrade (2004/2005) with the Royal Flemish Theatre and the National Theatre Walloon-Brussels community. The lay gathered marginalized people on stage, the so-called Invisibles (deleted, excluded from political and economic context), refugees from war-torn areas during the 1990s, the displaced, former military personnel, Roma people… as well as professional actors, dancers, and musicians with the idea to point out their problems on the scene of the National theatre in Belgrade and Brussels, and thus to make their stories – visible.

In the scope of the guided tour through the exhibition this Saturday, special attention will be paid to the play, and on this occasion we spoke with the playwright Ivana Momčilović.

Preparations for the play lasted almost four years. How the process of its creation looked like? How did you find the participants?

At the beginning of the Yugoslav war and in the midst of leaving the country that was falling apart, in 1991, I parted ways with fiction for almost 10 years. At the time, I thought that art could not do anything in traumatic, bestial situations, such as war and social chaos, and that art was ultimately – useless.

Those years I dedicated to joining political movements in the country of my exile, Belgium. At one of these meetings, I met director Lorent Wanson. After years of searching for new dramaturgical forms and political struggles, I realized that a factory and its circle is a really big scene, that every addressing of workers to workers, each process of stopping the work, every protest, carry within themselves a degree of theatricality, and I suggested to Lorent that we should make a play about Yugoslavia. Whirling around political struggles, or gravitating through them in search for new art forms, I began again to think about the power of fiction and poeticisation in the prosede of documentary. That gave rise to this play.

As far as participants are concerned, the professional part of the team consisted of actors that each of us, the director or I, suggested. With Esma Redžepova I worked already on the International Festival of Women’s Voice (Voix de femmes) in Belgium, and part of the team came at the suggestion of the National Theatre in Belgrade. When it comes to amateurs, i.e. the actors who played their own selves, we did not organize any audition for them. The assumption is that everyone has the potential for much more, and competition in tragedy would indeed be grotesque.

That part of the team I came by in different ways, the Surrealists would say “by the objective case“. Some of them came from a group of Roma who first went to seaside in Montenegro, with whom I travelled one year among them were refugees from Kosovo, while the other part consisted of Roma workers from Urban Sanitation. One day, I was going out from the rehearsal in the National Theatre, when I saw a group of street cleaners led by a policeman to a police van because the workers allegedly had stolen something. The men, in their working uniforms, claimed that all they carried were just their garbage bags and that they were just doing their job. (We later brought the scene on the same stage of the National Theatre).

One woman, who had seen many exhumations of bodies in search for her husband kidnapped in Kosovo, I met in a random visit to the Association of Single Mothers of Displaced Persons and Refugees, on the day when these women were offered free hairdressing services. She talked about the importance of the new ivory strands in her hair that had been unkempt for too long. On that occasion, I found a woman who told me the most incredible story with a touch of dignity and poetics of language: the story of the “gentle Reseda green” shirt of her husband. Such was the shirt in which her husband had been kidnapped and that colour was her rapper. She was looking for that, and not any other shade of green in the folds of foul-smelling fabric on the remains of corpses, (because, as she said, folds remain the “true shade”).

Ljubiša, the former JNA officer, who lived with his family in one room, I found by accident, when I got to a solitary hotel in Dorćol. Srđan, who was enrolled in 1991 to a regular military service, was found by the director and I while he was working as a waiter in a cafe in Belgrade. After mobilization, Srđan ended in a truck sent to the battlefield, got a handful of real bullets, and his whole squad was killed while he was on guard.

The most valuable element of the whole enterprise is to prove the hypothesis that any person, whoever they may be, has a poetic capacity, but in this case they have the capacity of actors as well. The amateur part of the team even, paradoxically, was in a way more professional than the professionals – all of them quickly remembered the lines, showed up on time, demonstrated exceptional motivation, ability, talent. Literally everyone. When they are motivated, once they have a reason, a catalyst, they are all ready for emancipation, all they need is a trigger.

Text for the play was emerging during work on the play, based on the testimony of participants. What did the process itself mean for you as the playwright and as a human being?

The process showed me that poetization and fiction are necessary links in treatment of reality. Fiction is a necessity, fiction is everywhere; there is something that, in my opinion, can be called materiality of fiction, necessity of fictive building materials to overcome reality, in search of a better and fairer world. I dedicated myself to a “feature” project, which really lasted long, but only as much as its preparation was supposed to last, i.e. as long as it was necessary to hear the invisible citizens of post-Yugoslav societies in the noise of the world, to gain confidence, to live, work, socialize, together. The whole process has led to the fact that this random collection of the Invisibles, which can be represented by many of the same or similar situations, became a specific, generic experience, with the result that cannot be calculated in advance, which is the important moment of treatment of the future. On the one hand, a stage of the National Theater in Belgrade gave them the necessary visibility, but on the other, working with that institution demonstrated that it was not ready to provide continuity in the minimum further concern for these people. In this sense, our project was not enough. We need fiction after fiction, too.

Why did you decide to use poetizing, as a mechanism for transformation of the documentary?

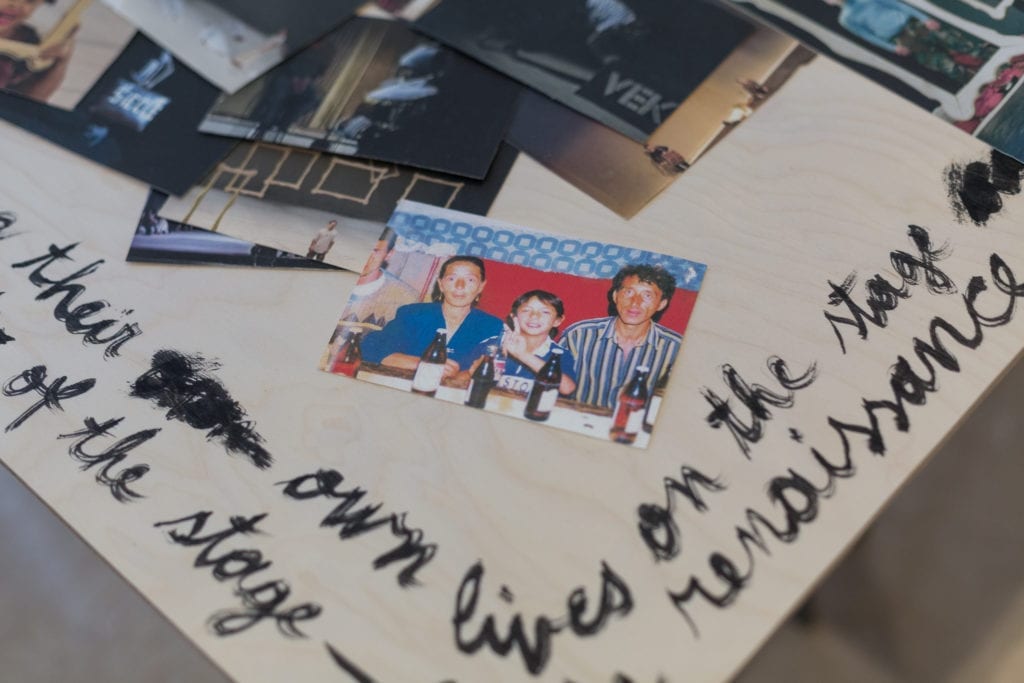

Just as Renaissance actors used transparent gauze on the proscenium as a “shield”, behind which they played to protect themselves from the onslaught of rotten tomatoes of their potentially disgruntled audience, poetization has shown itself to be a transparent shield for the people on stage who, in a kind of poetic personal stories, succeeded to enter the characters, where they were not alone, but together with all those who were in the same situation. They managed to tell from that place a universal story about those who can no longer be seen. Therefore, by poetizing we came to the position of universal, not particular stories/experiences, which is a way to upgrade the documentary, the existing. Moving towards the non-existent. Towards what is yet to come. Towards what is being dreamed of. Towards the things for which no one can know exactly what form, space and time they will take. That’s the beauty of the mysteries and wonders of the common life of the people on earth.

What kind of transformations on the stage did you witness when it comes to the actors, on the one hand, and the Invisibles, on the other hand?

The scenes where the people from real life explained to the cast their characters or the scenes where the actors played present Invisibles are those where we gave the amateurs freedom to stop the actors every time they thought that something was not realistic, and that the actors did not perform them realistically. Based on the dramaturgy of these breaks, I wrote the text, shaped it so that the participants could learn it later. These are the scenes that directly taught about life, this time from a stage, as from the large stage of life.

The scene where Ljiljana explains to the actress who plays her trying to identify the body of her husband, and the scene where a refugee from Croatia explains the actress, who plays her, how she was embarrassed because of the looks of people on the bus, might be something most precious I’ve ever seen in a theatre, in the sense of theatre as a large auxiliary scaffolding around the facade of life.

The play had its premiere in Belgrade and Brussels. What were the reactions of the local audience, and how it seemed to the viewers in Belgium?

The audience reacted strongly everywhere, because the play, according to the critics and viewers’ reaction, was a transformative experience, in terms of moving the boundaries of what one is capable of, what one was born for, in the sense of radical work on equality and relocation of roles assigned by life.

In Belgium, this play reunited two national theatres, which had never before worked together (National Flemish and Walloon National Theatre), in a kingdom that is constantly on the verge of nationalist chaos, just like Yugoslavia was. There, standing ovations might be even greater testimony to the recognition of the universal language of poeticisation of horrors and creating a common language for the impossible, which served as a basic dramaturgy of the play.

How much was the venue itself – the National Theatre in Belgrade – important for the visibility of topics problematized by Holes?

This question hits the target. The selection of the National Theatre (to the general consternation of many colleagues) was crucial for receiving “the people” on its stage, part of the nation exempt from the audience in the theatre, as well as from the actors on stage. In the Kingdom of Belgium, it was important to make the first collaboration (co-production) between National Wallonian and Flemish National Theatre, facing each other for decades, a few hundred meters away, with no experience of cooperation until the corpse of Yugoslavia showed up. Thus, the selection of the institutions was of great importance, I would say part of the general dramaturgy.

One question cannot be left without an answer – what are social achievements of art? What are your impressions? What did Holes mean for its actors, and what for its reception within the society in which those actors were invisible?

Thank you for this question. The experience of the play confirmed my indications of willingness/capacity of each person for art and the need for fiction, as a means of raising political, human struggle to a new level. So, in my point of view, it is no longer the dilemma called “leaving the art” or reduction of art to realistic (engaged) level, but something far more radical: the abandonment of the idea that political struggle and emancipation can exist without fictionalization, poeticisation, and we can say without aesthetic revolution without passing through the sensual, the upgrading of the real and surreal, as the necessary next level of reality.

Let us remember that the Movement of Non-Aligned was initially called the Movement of Non-Engaged countries and that the Havana Declaration, from 1979, stated that the movement strove to ensure “the national independence, sovereignty, territorial integrity of the non-aligned countries in their struggle against imperialism, colonialism, neo-colonialism, apartheid and racism, including Zionism, and all forms of foreign aggression, occupation, domination, interference and hegemony as well as against bloc politics.” It all works together as a beautiful social utopia, close to science fiction. However, it is the role of fiction to set the impossible in front of you and to work on the same stage hand in hand with reality, with the existent – on its realization. This movement was initially called the movement of “non-engaged, non-bloc countries”, but it went further, changing the name to “non-aligned” in the search for a new name, starting from non-existent that will treat the existent. Our play has both perspectives in its name. Holes or When We Were Not Aligned

What happened to the participants after all these years? Have you been in contact with them?

Yes, I’ve stayed in touch with many of them, especially with the Roma part of the team. Of the whole group (six of them), only one is still in Belgrade. As he said, “Where else would I be, I’m still in the Urban Sanitation.” Others have emigrated, of course mostly on foot, crossing the border illegally, paying to be taken to the so-called free territory of Hungary at the time, but not every time successfully, and not from the first try, usually for a huge amount of money. In part, the reason for that was the fact that we in the play had a scene of an embassy, where those who wanted to stay in Belgium said so on stage, so from the start it was clear that many of the actors had a strong motivation to participate in this long process because they wanted to stay in Belgium. However, the institutional outcome was not possible, and yet these people stayed on their own and continued with their illegal border crossings. Many of them now live in Germany, one is even in the US, so they used a new kind of fiction, beyond our boundaries and borders that we developed together, to come to a paradox where institution limited fiction. I’ve been in contact with other participants, as well. The exhibition The Nineties: A Glossary of Migrations, in the Museum of Yugoslavia, definitely is a nice opportunity to get together again.

For more information about the exhibition Nineties: A Glossary of Migrations, please visit https://www.muzej-jugoslavije.org/exhibition/devedesete-recnik-migracija/.

The Origins: The Background for Understanding the Museum of Yugoslavia

Creation of a European type of museum was affected by a number of practices and concepts of collecting, storing and usage of items.

New Mappings of Europe

Museum Laboratory

Starting from the Museum collection as the main source for researching social phenomena and historical moments important for understanding the experience of life in Yugoslavia, the exhibition examines the Yugoslav heritage and the institution of the Museum