A BRIEF FAMILY HISTORY

I remember a television interview with film director Aleksandar Petrović, from several years ago. He was going along the road between Belgrade and Pančevo, explaining that it was “his world,” highlighting the landscape as something that significantly determined his poetics. I was stunned. I couldn’t believe it. Aleksandar Petrović was a very important person for me, one of the main representatives of the Yugoslav cinema’s Black Wave, a phenomenon that was perhaps the crowning achievement of the country’s overall art scene during the 1960s and early 1970s. The Black Wave was a proof that in a socialist country, it was possible to create strong, impressive and very critical creative poetics, which opened space for achievements that were avant-garde and sometimes perceived as too liberal, even in Western countries. These films were funded by state money, and at various times were vilified and celebrated, pushed under the carpet, or highlighted as significant artistic achievements. How could, then, someone like Aleksandar Petrović single out that area around the road, where there was nothing special, with only a few gloomy industrial plants, some houses, and an endless plain bordered by swamps, how could that have any importance, attraction, anything? The reason for my surprise was the fact that this road was actually very important to someone, as a stage of life and death, for one family, my family.

My maternal grandparents, Petar and Spasenija Pavkov, settled in Krnjača in 1934, a place right next to the road that leads from Belgrade to Pančevo. There, they owned a tavern that had a secret partition somewhere in the interior, leading to a hidden room. I knew that members of the secret resistance movement were hidden there during the war, as well as anti-fascist literature, food, medicine and weapons, waiting to be transported along the Danube to partisan units, or in directions where they were needed. Only recently did I find out that my grandfather had a code name, ‘Dragi’. These were all dangerous activities, which almost cost them their lives when they were discovered by Nazi agents.

Petar Pavkov; Courtesy of Saša Rakezić

A few years ago, I dreamed of my grandfather, Petar Pavkov. His face seemed very real as he stood motionless, looking directly into my eyes. In my dream, I felt my eyes filling with tears. I heard myself saying, “I was only fourteen when you left. I didn’t get a chance to ask you everything I should have.” Later, I realized that it really summed up my feelings at the time. My grandfather died of cancer when I was fourteen. It was 1977, and I was the only kid around who was enchanted by avant-garde art movements from the turn of the century, plus I didn’t know anyone in my immediate surroundings who saw something, hmmm, “special”, if not revolutionary, in the emergence of the original punk, and these were my preoccupations at the times. Although I knew about the activities of my grandparents during the war, the war then seemed like something foggy, far away, and connected to some legendary past. Besides, my grandparents almost never talked about it, although, especially from the point of view of today’s conformism, their actions could be called selfless, even heroic. I loved them, with the simple soul of a child, and that was all. When I wasn’t looking at the world around me with curiosity, I was engrossed in reading comics, and my grandparents didn’t see anything wrong with that. Spasenija, and especially Petar, had many friends, and I remember that acquaintances always came around their house, talking for hours on end about life, about past times, or just about anything. Now I realize that there were a lot of interesting stories, which I wish I had had enough wit to record.

Petar, Olga, Milanka i Spasenija pedesetih; Iz foto-arhive Saše Rakezića

I recall my grandfather spent a long time patiently listening to a distant relative, who worked as a night watchman in a factory, and claimed to know the language of animals and the secrets of flying saucers. It seemed to me that my grandfather did not believe him, but listened respectfully and without interruption to every wild tale in which this man earnestly described the most incredible details. I still nurture a deep sense of gratitude because I was able to share that time of my life with those people. Also, I knew that my grandfather, despite his heroic activities during the Nazi occupation, spent the period 1950-1952 on Goli Otok as a political detainee. Still, I never noticed any trace of resentment in him, and now I believe that he had good reason to be – he found himself on the opposite side of the mainstream tendencies in the country, and that was certainly painful. Maybe he tried to spare his grandchildren all those stories, but even at the time when he was ill with cancer, sometimes he seemed tired, but not angry. Still today, I remember his sonorous laughter, which, after all these years, I can hear so clearly in my mind.

MOVING TO KRNJAČA

Who were our ancestors; do we easily forget their life stories; how did they cope with the dramatic reversals of historical events, which, especially in the Balkans, were too many to count? Can we draw any conclusions from their experience, even after they have disappeared from the reality we inhabit? I tried to answer some of the questions I asked myself, maybe to make up for all that I missed in my immaturity… Therefore, I looked for information about my family in the Pančevo archives, and in the Archive Collection of the Museum of Vojvodina in Novi Sad – as well as in dozens of books dealing with the Nazi occupation of Serbia, adding to that everything I noted in conversations with relatives and acquaintances…

Petar and Spasenija Pavkov came from the vicinity of Sremska Mitrovica (villages Laćarak and Kuzmin), about 70 kilometers from Belgrade, and it’s known that Petar got a job in a tannin factory in 1926, where he soon became a trade union activist. They moved to Krnjača in 1934, and opened a tavern not far from the bridge on the Danube. The tavern was called “Kod Pere Sremca” (At Pera Sremac). Although they had come from the Srem area, and had relatives there, I knew little about their life there, or the reasons why they moved to the district between Belgrade and Pančevo. However, the fire of my imagination has always been kindled by the fact that Sremska Mitrovica was built upon the important ancient city of Sirmium, which was declared one of the four capitals of the Roman Empire at the end of the 3rd century, during the Tetrarchy. The modern city has covered the remnants of the ancient one, pushing the mysterious layers deeper into the unknown. At the beginning of the 1970s, American enthusiasts came up with the idea to move the entire population of Sremska Mitrovica to a new location in order to fully explore the ancient ruins. For my grandparents, however, moving from the vicinity of Sremska Mitrovica to Krnjača in the 1930s probably meant getting closer to the economically more prosperous Yugoslav capital, where they could independently engage in business. This was at the time when, with the construction of the bridge on the Danube, a suburban settlement was created around Belgrade on the other bank, in the Banat area that gravitated towards Pančevo, previously traveled to exclusively by boat. At the beginning of the century, Krnjača was sparsely populated, often flooded, but thanks to the land reclamation of the area, the so-called Pančevački rit, carried out by a French company in the period 1929-1933, the number of immigrants grew. In the early 1930s, Đorđe Lobačev, perhaps the most famous comic book artist of the pre-war Belgrade, who then temporarily settled in Pančevo, also worked on the construction of the embankment in Pančevački rit. He described this in his autobiography, where he also talked about the visit of the French company’s CEO, when a team of subcontractors, composed of Russian refugees, Cossacks, who worked on the embankment and the road to Pančevo, were marshaled. Dressed in their ceremonial suits, with wolf-skin hats, bandoliers on their chests, and glorious decorations, the Cossacks saluted during the inspection, holding shovels in their hands instead of rifles! Representatives of the French company watched in astonishment, while the Yugoslav and French anthems were broadcast in the background.

With the communal regulation of this area, a significant number of people from various districts moved there, and given the lower taxes than in the center of the capital, Krnjača became a destination known for its taverns, where, with the establishment of railway and bus traffic over the bridge, mostly poorer residents of Belgrade could afford a lunch at a lower price and enjoy the music of numerous bands. Petar Pavkov soon came into contact with a group in favor of the Communist Party (and other parties of the Left), gathered at the University of Belgrade. Among the people he worked with were prominent intellectuals, such as Bora Baruh – born in the same year, 1911, they were both only a few years older than most of the young rebels they knew, but at the time the age difference was considered as significant.

Bora Baruh came from a family of Sephardic Jews in Belgrade (his real name was Baruh Baruh, but he is remembered by his Serbianized name, Bora), and was a noted painter. While on his academic specialization in Paris in the second half of the 1930s, he recruited Yugoslav volunteers and organized their departure to Spain, where they fought on the side of the anti-Francoists, until the French authorities found out and returned him to Belgrade.

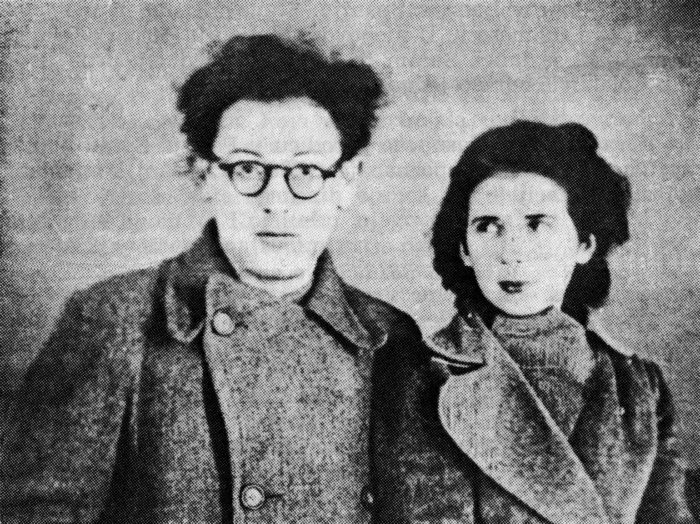

Bora Baruh and Elvira in Belgrade, 1938; Courtesy of Saša Rakezić

Bora and his brothers, Isidor and Josip, were beloved figures of the resistance against the Nazi occupation, and they all died in that fight, as did their sisters Rašela and Berta, shot by the occupiers, while their sister Sonja was the only survivor of the war.

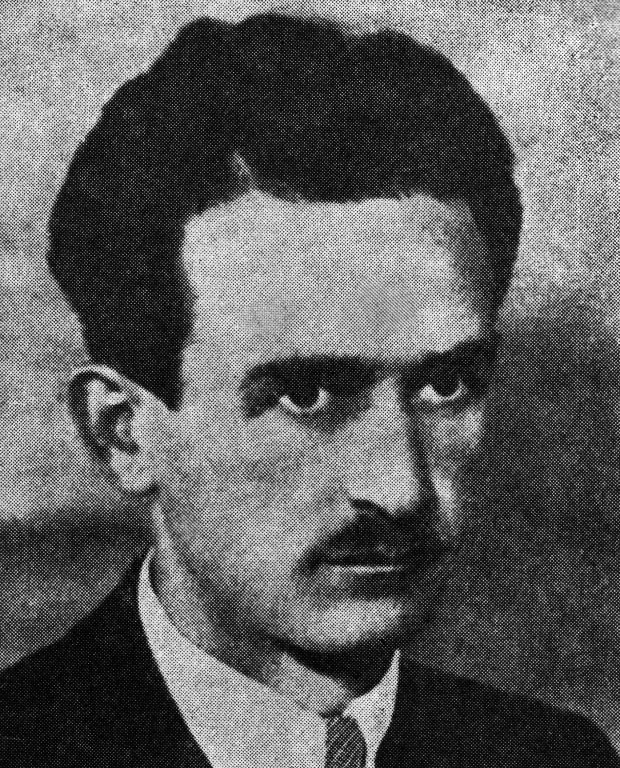

Gligorije Ernjaković; Courtesy of Saša Rakezić

Then, Petar collaborated with Gligorij Ernjaković (a famous translator, who later translated Kant, Nietzsche, Felix Kanitz’s writings on the 19th-century Serbia, and even Kierkegaard directly from Danish!) and Veljko Kovačević – who was close to Social Democrats before the war, and after the war was a defendant at the trial of an organization called the Alliance of Democratic Youth of Yugoslavia (1948), to which the famous writer Borislav Pekić also belonged. Even later, Kovačević was also the lawyer of perhaps the most famous Yugoslav dissidents, Milovan Đilas and Mihajlo Mihajlov. In this company, Petar also met Svetozar Vukmanović Tempo, who was an important figure during the preparations for the student protests at the University in pre-war Belgrade. During the war, Tempo, among other things, worked on the formation of illegal printing houses and was among the main organizers of the resistance movement, and after the war he became one of the new government’s leading officials. After publishing his autobiography in 1971, one of the rare confessional prose writings of a high-ranking Yugoslav official, he lived a rather secluded life, although in 1986 he accepted Goran Bregović’s invitation to participate in the recording of Bregović’s band Bijelo dugme’s song “Pljuni i zapjevaj, moja Jugoslavijo” (Spit Out and Sing, my Poor Yugoslavia). At the beginning of this song, the harsh verses of which could be interpreted as a kind of prophecy of the collapse of the country that would happen during the 1990s, Tempo sang a part of the revolutionary song “Padaj silo i nepravdo” (Down with Force and Injustice).

Since it was accused of plotting subversive activities, the Communist Party had been banned in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia since 1920. Acting illegally, people whom Petar Pavkov met were forced to hide from the police from time to time – as a family man and innkeeper in Krnjača, he probably didn’t attract the attention of the authorities, which mainly dealt with students prone to excesses. The Pavkov’s tavern and house soon became a gathering place for many interesting characters, who saw themselves as fighters against the capitalist establishment of the time, and it was probably then that the idea of a secret room in case of danger arose. My grandmother, Spasenija, soon joined these activities as a courier – she carried confidential documents in double-bottomed milk buckets, which sometimes had to be hidden from police raids.

Double-bottomed vessels, similar to those used by Spasenija; Courtesy of Saša Rakezić

Their activity quickly expanded to collecting and preparing food, which they forwarded in packages to political prisoners. It took a lot of time and organization, but it showed that, at the family level, despite the fact that my uncle Borivoje was born in 1938, something could be done for “the cause” as well.

OCCUPATION

Perhaps, thanks to their experience in conspiratorial activities, all their work was, in somewhat changed circumstances, continued and expanded during the occupation. Despite the drama that surrounded them, Petar and Spasenija had twins in December 1941, Milanka – my mother, and Milan, who got sick in those war circumstances and died a year later. My mom claimed that, because of that, she felt a hard-to-describe melancholy all her life. My grandmother told me that, among all the events of that turbulent time, she also had appendicitis. Instead of anesthesia, which was difficult to come by during the occupation, before the operation, that is, before they cut her abdomen, they gave her to drink a bit of rakija… Immediately after the end of the war, Petar and Spasenija got Olga, in 1946. And life went on…

But a lot happened between the beginning and the end of the war, a whole novel could be written just about that. First of all, there could be a lot of talk about how the world war crept into these parts. After the Nazi invasion of France in June 1940, it became clear that the Great Britain would not be conquered in a short time, so Hitler’s Germany had to secure its positions in the Balkans, and thus prevent an attack from the direction of the European southeast. Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria joined the Triple Alliance, and the same was expected of Yugoslavia, which suffered considerable pressure from the Nazis. On March 25, 1941 in Vienna, the Yugoslav government and Prince Pavle Karađorđević, the Crown’s representative instead of the then minor King Petar II Karađorđević, signed Yugoslavia’s accession to the Triple Alliance. The very next night, that decision was annulled – after a coup carried out by high-ranking officers, the government was overthrown and power was handed over to the eighteen-year-old King, Petar II, and the government was run by rebels. On March 27, large-scale demonstrations broke out in Belgrade, expressing popular support for the putschists, and refusal to join the Axis forces. Protests broke out in several Serbian cities, as well as in Sarajevo, Ljubljana and elsewhere. It was a very brave expression of the disapproval of a small European nation, at the moment when the Third Reich was at the peak of its upswing, on the march towards world domination. There was a feeling in the air that the Nazis would vent their anger fiercely, and Hitler personally stated that “Yugoslavia would be destroyed,” and asked for military assistance from Italy, Hungary and Bulgaria as soon as possible, in return for part of Yugoslav territory. Without notice, Belgrade was bombed on April 6, in the early morning hours. Up to that time, it was one of the most extensive bombings of a city area in history. On that day alone, carpet bombing was carried out on four occasions and continued throughout the night. In addition to military targets, residential areas and numerous public institutions were bombed. One of the goals was the National Library, in which, along with a large number of books and invaluable manuscripts from the Middle Ages to the modern age, the entire magazine production, which contained all comics magazines published in the previous period, burned down. Although it was only one of the countless other losses, it resulted in the suppression of a very interesting and lively comic scene that was created in the 1930s in Belgrade, in the Balkans, and which was completely in line with modern tendencies of that time. It took decades for that curious comics production to recover from the loss.

Basically, Belgrade looked like a post-apocalyptic incinerator, corpses were everywhere in the city, and thousands of people leaving the city were exposed to bombs and machine gun fire from the air the next morning. The rebel government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, just established, had a hard time dealing with the overwhelming force, and the Yugoslav army was falling apart – citizens and soldiers from different Yugoslav provinces rushed towards particular interests related to different national and religious identities. It was the first disintegration of Yugoslavia, which would happen again during the 1990s, exactly fifty years later. Pressed by superior enemies, the Yugoslav army retreated, chaotically.

Near the demolished Pančevo bridge, 1941. Courtesy of Saša Rakezić

In an effort to slow down the Nazi advance, bridges around Belgrade were demolished, including the one on the Danube, named after the adolescent King Petar II, which everyone called the “Pančevo Bridge,” not far from the tavern run by my grandparents.

At the time of the bombing of Belgrade, the Italian writer Curzio Malaparte was staying in Pančevo, where this event could also be experienced (at least from a certain distance), and he described it in his perhaps most important work, entitled Kaputt. When the bridge was already demolished, the writer stayed for three days in the area called Pančevački rit, to which the small town of Krnjača also belonged. He wrote that it had been located directly opposite the collapsed bridge, which was close to the place where my grandparents lived, but – who could tell if he drank rakija or had dinner in the tavern, which was then run by my grandmother (my grandfather was recruited into the Yugoslav army, then captured by the Nazis, but before being transported to military camps in Germany, he managed to escape and return to his home). In any case, masterfully mixing fiction and descriptions of the scenes he experienced, Malaparte noted the horror that hovered over that landscape,

“I had to stay in Pančevo for three days. Then we moved on, crossed the Tamiš, crossed the peninsula where the Tamiš was at the confluence with the Danube, and stayed for another three days in Rit, on the banks of the great river, just across from Belgrade, next to the iron structures of the collapsed bridge named after King Peter II. Burnt logs, mattresses, dead horses, sheep, cattle swirled along the yellow and fast current of the Danube. In front of us, on the other shore, the city exhaled in mortal agony, with the sweet smell of spring spreading all around…

“Finally, one evening, before the sun went down, Captain Klingberg crossed the Danube and captured Belgrade in a boat with four soldiers. Then we crossed the Danube under the ceremonial protection of Field Marshal Grossdeutschland Division, which managed the river traffic (lonely, clean, important, imaginative, that field ship that stood on the bank of the Danube, the only unlimited space of huge traffic of people and vehicles on this river, looked like a Doric pillar) and we entered the city near the Danube station, at the end of Kneza Pavla Street.

“A green wind played among the leaves. The sun was about to set, the last light of the day poured from the gray-bluish sky like extinguished ashes. I passed stopped trams and taxis full of corpses.

Belgrade after the bombing on April 6, 1941; Photo: Museum of Yugoslavia

Fat cats, squatting on pillows next to dead bodies already blue and bloated, stared at me with slanted eyes of phosphorescent shine. A yellow cat was following me for a long time on the sidewalk, meowing. I stomped on the layer of broken glass, shards crackling terribly under my shoes. Occasionally, I would come across a passer-by sneaking along the walls and turning suspiciously in all directions. My questions remained unanswered: everyone’s eyes were strangely blank as they ran headlong. Their dirty faces did not reflect fear, but astonishment.

“It was still half an hour until curfew. In front of the Balkan Hotel, next to a huge bomb crater, there was a bus full of victims. On the Republic Square, near the monument, the National Theater was still burning…”

After the Kingdom of Yugoslavia ceased to exist, about 300,000 mostly Serb soldiers and officers were taken to prison camps. Serbia was cut into pieces – the central part, together with Belgrade, was under German military rule, and other parts were under Croatian, Hungarian, Bulgarian and Italian occupation. Banat was a separate political entity within Serbia under German rule, governed by members of the German national minority. Pančevo, with a large German population (who called themselves Danube Swabians or Volksdeutscher), was part of that new reality, and Banat was administratively annexed to Pančevo rit with Krnjača. The Nazis quickly began to carry out their program, which included the persecution and extermination of Jews and Roma (after the majority of the Jewish population was gathered in camps and then systematically killed, in May 1942 it was announced that the territory of Serbia was, under German rule, Judenfrei). Jovan Rajs (today, one of the most famous forensic scientists in Sweden), then an eight-year-old boy in 1941, living in Petrovgrad (today Zrenjanin), testified in his autobiography, “The Plenipotentiary of the Silent”, about the harassment of the Banat Jews by their Volksdeutscher neighbors immediately after the occupation.

“Those who were arrested lived in my school, Central School, and from there they went to work on clearing the ruins that were on the outskirts of the city… Sometimes Dad would get permission to come home in the evening, and occasionally he would spend the night at the house. He said that they attended various ‘performances’. ‘What kind of performances?’ We, the children, asked. But he didn’t want to talk about it.

“Today, I know what it was. In the evening, the guards would organize various types of entertainment, and members of the German Kulturbund and their wives and children also attended these performances. Jewish prisoners were in charge of the program. The performances usually began with various anti-Jewish songs in which Jews were ridiculed and threatened with beatings, while the courage of the German people was glorified. It was followed by other ‘fun’ points of the program. The old Jews had to crawl around the room on all fours, turn somersaults or ride each other, and so on. The performances would usually end with a dance. Both guards and Jews took part in the dance. The Jews had to strip naked and play polka, foxtrot and similar dances in the middle of the room in the presence of German soldiers and Banat Swabians, while the guards trampled on their bare feet with their hobnailed boots, until they were completely bloody.”

THE TIME OF RESISTANCE

Of course, all anti-fascist citizens were under attack by the occupation authorities and the police. Considering that the guerrilla resistance began in Serbia in the middle of 1941, a draconian method of punishment was introduced – one hundred Serbs were shot for every German soldier killed, and fifty for any wounded. Thousands of hostages were massacred in central Serbia. As the majority of the German army had already been sent to the Eastern Front, the special police and gendarmerie were formed by the puppet government, the leader of which was Quisling Milan Nedić. In the midst of this chaos, there was a kind of anti-fascist underground resistance through conspiratorial activity, and activists of that kind were called “illegals”.

In the spring of 1941, when, after escaping captivity, Petar returned to his home and tavern, the situation had already changed. In physical terms, the destruction of the Pančevo Bridge on the Danube, about a kilometer and a half long, distanced Krnjača from Belgrade, not only because it was administratively annexed to the Banat area, but also because each ferry or boat crossing required documents issued by the occupation authorities. There were people who got those documents a little easier, for example if they moved from one territory to another for work or if they worked in the fields, but they were a minority. The situation was particularly difficult for those who had already been labeled as political activists or were Jews. Petar’s friend and brother-in-arms, Bora Baruh, was both. Although he had notable exhibitions in the country and abroad during the pre-war period, he was often arrested and detained as a member of the banned Communist Party. After the bombing of Belgrade in April 1941, he was sent by the occupation authorities, together with other Jews, to clear the ruins and extract the corpses.

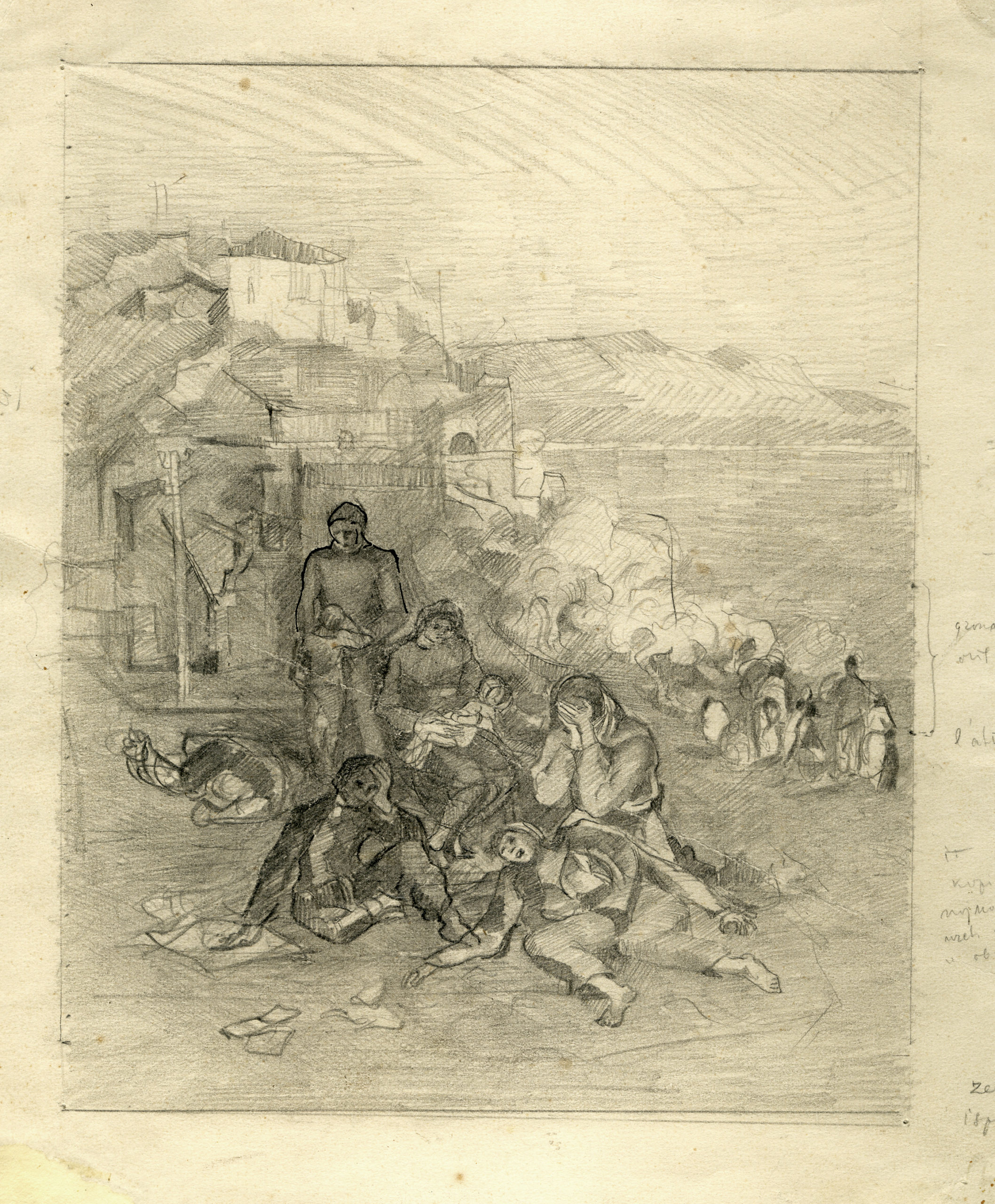

Bora Baruh, Refuge on the Ruins, 1941; Photo: Museum of Yugoslavia

After a large ammunition depot built by the Nazis within the medieval fortress in Smederevo exploded, under still-unexplained circumstances, a huge area of that city was destroyed, along with part of an important monument from the Middle Ages. Large numbers of people were killed because the crowded local train, which was typically always late, was passing there at the very moment of the explosion. After the catastrophe, about 600 Jews were brought to Smederevo for the purpose of cleaning the debris, among whom was Bora Baruh, who managed to escape from there and return to Belgrade through secret channels. Most of the Jews, however, were deported to camps immediately after the hard work. In his hometown of Belgrade, Bora, together with his French wife Elvira, and their four-year-old son Jean-Claude, he managed to hide for some time, although for security reasons they were often separated, hiding at different locations. In August 1941, Bora Baruh joined the partisans, and in November he arrived in Užice, where the first free territory, the Republic of Užice, was founded at the end of September. There, Bora found out about the deaths of his brothers, Isa and Joža Baruh. At the time, with several artists, he formed a studio, which was engaged in scenography for theater performances as well as the production of posters and illustrations for newspapers published in the liberated Užice. However, this did not last long, as the Nazi forces, with significant reinforcements arriving from other fronts, suppressed the partisan units. In March 1942, Bora Baruh was in a group of partisans who were surrounded and captured, and after that he was remembered as someone who was, between beatings and continuous interrogations, incessantly drawing. One of the witnesses described Bora’s behavior as follows, in the break between severe beatings,

“I was locked in a room in the basement of the Gestapo building in Belgrade. One day, they brought Bora Baruh, all torn and bruised. He was wearing an old Serbian suit, and boots with no soles…

“Some time passed, and Bora took a piece of paper out of his pocket and started drawing his boots. I admired his skill. Seeing this, the guards asked him to draw them.”

One of the testimonies referred to Bora’s confession regarding the anguish he felt when he was forced to draw portraits of his torturers. His life ended after his detention in the Banjica camp near Belgrade, from where he was taken to be shot.

Bora Baruh was just one of Peter Pavkov’s comrades with whom it was no longer possible to maintain contact – many of them were forced even deeper underground if they stayed in the cities, or they joined partisan units, going deep into the wooded areas of the Balkans, avoiding the main routes controlled by the Nazis. Krnjača was a place with two or three thousand inhabitants, among whom were about thirty young people who gathered to plan sabotage against the occupiers. However, in such a small environment the information quickly reached the police, which made arrests on several occasions, and after interrogation sentenced some of the prominent individuals to shooting. Small groups of several associates had been formed, acting independently of each other.

Zaga Malivuk; Courtesy of Saša Rakezić

Among the activists in Krnjača whom Petar Pavkov knew, was Zaga Malivuk, who consciously avoided contact and cooperation even with potential like-minded people, because she performed an important task as a courier for the Headquarters, headed by resistance leaders in Serbia. Since the occupying government used severe forms of torture on young people who it suspected, it was better that even reliable people didn’t know anything about her activities. In her early twenties, from a family of modest means, Zaga Malivuk was unknown to the police, and therefore a useful collaborator for performing such a responsible task… She gained the trust of her superiors, whose secret apartments she knew about, by managing to secretly come up with plans for a new type of Yugoslav aircraft, immediately after the occupation began, in the aircraft factory “Rogožarski” where she was employed; also, she destroyed those plans, preventing them from falling into the hands of the occupiers. By the end of 1941, at the moment when there were a series of arrests in Belgrade, it was decided that further courier work of Zaga Malivuk would be too risky and, just when she was about to be moved to a partisan unit in the interior, her landlady reported her to the Special Police. She was arrested with all the confidential materials, which she had put in her bag in order to escape the city. After heroically enduring beatings and torture during several interrogations, Zaga Malivuk was transferred to the Banjica camp, and then shot in July 1942. In the fall of the same year, her brother was tried for killing, in anguish, the landlady who reported Zaga. The woman had worked as a midwife, and actually was in a romantic relationship with Zaga’s brother.

Besides the fact that today we know that, despite the horrible tortures, Zaga Malivuk did not reveal any of her associates, she is also known for organizing one of the most bizarre events in the Banjica camp. Given that a large number of prisoners did not survive their stay in Banjica, there were few witnesses to recall the course of events, but it is basically a story of Zaga who, despite the atmosphere of hopelessness that prevailed there, tried to raise people’s morale in the camp. Together with other prisoners, she suggested that they organize a masquerade in cell number 16. Zaga was good at drawing and soon masks were created representing caricatures of the guards, and then prisoners acted the details of life in prison in various scenes. Using the materials they managed to collect, among other things, they made masks of Charlie Chaplin, Pat and Patachon (heroes of Danish comedies from the pre-war period), and also Donald Duck. The poster for the performance, which was placed on the wall, showed one of the camp guards, kindly inviting from his car a prisoner to join him for the ride. A dance followed, and combs served as musical instruments… The guards found out about these events, and beat the organizers, who soon after found themselves in front of a firing squad.

FOOD FOR PRISONERS

However, during 1941, journalist and publicist Dušan Bogdanović, who would significantly influence Petar Pavkov, moved to Krnjača. At the beginning of the century, Bogdanović had studied philosophy in Leipzig, and then moved to Switzerland during the tempestuous 1915, and then to the United States, where he worked among emigrants on agitating volunteers to join the Serbian army in the World War I. Between the two wars, he settled in Belgrade, and in 1940 he became the vice president of the People’s Peasant Party, which was the most left-wing of all the parties that were legally allowed in Parliament. After the outbreak of the war, Dušan Bogdanović considered it necessary to join the communist resistance movement, and he did so by direct action. Already in his fifties, immediately after arriving to Krnjača, he met Petar Pavkov, who – even though he wasn’t the member of the Communist Party at that time – demanded of him to send him, through his connections with the top of the resistance movement, somewhere where he could better serve the fight against the occupiers. However, Bogdanović suggested that Petar should stay in Krnjača and be a courier who would organize the transfer of important information, and it was likely that even then people continued to hide, if necessary, in a secret room in the tavern. Taverns were a good place to hide, because all walks of life passed by and gathered there, but a deadly game of cat and mouse also ensued, since among those gathered there hostile elements could be found.

Shortly after the Banjica camp was formed by the military command and the SS administration (with the help of Nedić’s collaborators) in the summer of 1941, Dušan Bogdanović and Petar Pavkov began collecting food that eventually was distributed to the camp prisoners through organized channels. Generally, with minor interruptions, during all the years of occupation, Banjica prisoners were allowed to receive packages. Different types of food were collected from the village near Pančevo, in which one of the main associates was Dragomir Milosavljević from Banatski Brestovac, a member of the main board of the People’s Peasant Party. Milosavljević was suspicious of the Volksdeutscher police and was arrested several times, then tortured during the interrogation, but since he endured all that in silence, they never managed to determine his activities exactly. Based on only sparse information, it was difficult to reconstruct the actions of food delivery, but they were certainly associated with a huge risk, since the occupation authorities prohibited this type of activity. The aggravating circumstance was that, in order to transport a larger amount of food or any goods, it was necessary to have documents for transport on the entire length of the road, which included boarding a strictly controlled ferry, since the bridge on the Danube was under the river. However, by all accounts, it was a well-coordinated action, since the food was first delivered to Pančevo, where Dušan Bogdanović’s associates forwarded it to Krnjača. In Krnjača, there were several women who processed food if necessary (in some periods, it was allowed to supply only cooked food), and my grandmother Spasenija was among them.

In a statement given by Petar Pavkov in 1957, when testimonies of members of the resistance movement were recorded in Pančevo, he said that ‘Jelena’, from the Belgrade side of the river (possibly they didn’t even know her last name due to secrecy), had played a certain role, as well as an unnamed German officer (apparently an associate of the movement), who transported the collected food, sorted and deposited in Krnjača, by truck to Belgrade and further distributed it to the families of the prisoners. In his statement, Petar said, “They would distribute groceries there; to each woman a few kilograms of lard, bread or something else, and they later (in packages) individually carried it to the camp. This organized forwarding of food for Banjica lasted until the arrest of Dušan Bogdanović. Besides Banjica, we also supplied food to partisan units in Srem.”

All this was important because the food in the camps during the occupation was awful and a large number of prisoners died of hunger and exhaustion. During the war, even the majority of the ordinary population lived in poverty and destitution, and people in different types of detention were brought to the limit of human endurance. It is also known that the packages were looted by the guards, who kept better portions or any tobacco for themselves. However, by allowing detainees to receive (at least occasionally) packages, the camp authorities believed they were saving their own military economy, and those who wanted to deliver aid had to find ways to seize the opportunity, despite every conceivable limitation.

Although this type of (albeit secret) humanitarian activity has remained insufficiently studied, other examples in Serbia are known. For example, in the village of Kusiće near Veliko Gradište, during 1942 and 1943, secret production of Trappista cheese was organized in a cellar, in rolls suitable for delivery in a package. It was later sent to prisoners not only in the camp in Banjica, but also in Dachau and Auschwitz. Assistance in the distribution of this food was provided by two associates, members of Nedić’s collaborationist guard, who carried the cheese in backpacks; they were allowed to move freely because they had documents for shipping to Belgrade. Of course, a group for packing and delivery of packages was organized in Belgrade as well.

In any case, Dušan Bogdanović was arrested in 1943, and then he arrived in the same Banjica camp whose prisoners he had previously helped. He was shot in September 1944, shortly before the liberation of the camp the following month. During his imprisonment, Bogdanović showed great strength and dignity, and after he was summoned with several others to go to the place of execution, they told the guards that they would receive the deserved punishment from their own people (Nedić’s policemen were on guard duty in Banjica, while decisions were made by the representatives of the occupying power), after which the order “Stab!” was exclaimed, so that they were stabbed with knives before being put in a car and later finished off with shooting. “As far as I know, Dušan Bogdanović was seen as the president of Serbia even before the end of the war,” said Petar Pavkov. “I heard it in the speech of Siniša Stanković (biologist, president of the People’s Liberation Front of Belgrade, and a prisoner in Banjica) during the liberation of Belgrade, when he explained that it was not really his position, that Dušan Bogdanović should have gotten it in his stead.”

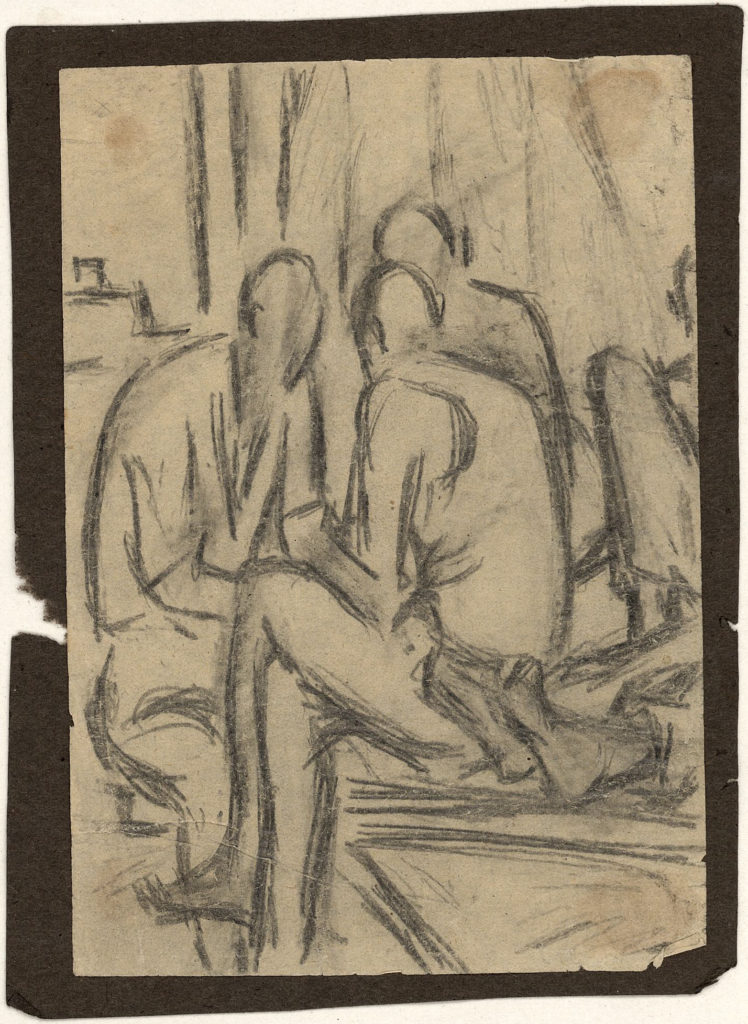

A portrait of Dušan Bogdanović from the Banjica camp, as well as a drawing of him preparing food for the prisoners, testifies to his role as a room elder. Thanks to the self-organization of the prisoners, and in order to avoid leaving without food any inmates who did not receive packages, it was decided that the packages, which could be received only once a week, on Wednesday, were to be equally distributed to all who were sharing a room. Decisions were made by a room elder, and so Dušan Bogdanović got the opportunity to take care of the food deliveries again, but this time as one of the prisoners…

It is interesting that the creator of the drawings depicting Bogdanović is Miloš Bajić, one of the prisoners who were interned in Mauthausen after Banjica, where he continued to draw whenever possible; he preserved about 150 drawings by burying them and then went to look for them after the liberation of the camp (these drawings would reach courts in Germany in the 1960s, as evidence against fugitive Nazis).

Miloš Bajić, Room Circle of Prisoners in Banjica, 1943/1944; Photo: Museum of Yugoslavia

According to the statement that was recorded, in the camp in Banjica, Miloš Bajić drew on toilet paper, on blank space in newspapers, or on the paper in which packages were wrapped. Drawing was forbidden in the camps, so the drawings that were preserved were those that other inmates managed to smuggle in their shoes, hidden in their hair, and the like. Miloš is the father of the well-known director Darko Bajić, who made a documentary in 2019, Line of Life, dedicated to the artistic work of Miloš Bajić in concentration camps.

SECRET NETWORK

At the time before he was arrested, Dušan Bogdanović, by the end of 1942, mediated the transfer of Stojan Orelj to Krnjača, who had previously been in a partisan unit in Western Serbia.

Stojan Orelj; Courtesy of Saša Rakezić

Orelj, whose code name was Relja, was a student of the Faculty of Philosophy before the war, and after an offensive was carried out in the fall of 1941 on territory liberated by the partisans, he managed to avoid arrest and stay in Zemun and Banat as an illegal; it’s even recorded that he hid for a while in a flat of Branko Gavela, the famous archaelogist… After that, he was transferred to Krnjača, where he met Petar Pavkov, and they became close associates. Thanks to the connections in the company that dealt with the control of waterways (it turned out that the director was a sympathizer of the resistance movement), Orelj found employment in the Water Control Community in Pančevo. It was a great improvement, as he managed to obtain papers that allowed movement even during the night, not only for himself, but for Petar Pavkov and all others that were connected with Orelj’s activities.

At the time, the situation in Pančevo was difficult. In the city where half of the population was of German origin, residents who immigrated in the 18th century (until 1918 Pančevo was part of Austria-Hungary), there was considerable resistance, until a few years before the war, to the pressure of the German propaganda to adhere to the Nazi ideology. It was especially opposed by the older population, who did not want to come into conflict with their neighbors of other nationalities. However, Germany had grown to the level of a superpower and among the young, Nazism, despite its ominous manifestations, became a symbol of something promising. One of the main proponents of Nazism was a doctor from Pančevo, Jakob Awender, who led a group called the Erneuerer, which published several pro-Nazi papers, all of which were issued in Pančevo (the most famous was Volksruff). As early as 1934, the Erneuerer tried to take over the main role in the clubs of the German national minority (Kulturbund). However, the end result was that the organizations of the German national minority distanced themselves from the Erneuerer, until 1938, when strict instructions arrived from Berlin that they must be given the right of priority.

As early as 1939, the Erneuerer held all important board functions of this national minority, although Awender was not elected leader of the Yugoslav Volksdeutscher, in order to avoid direct confrontation with the local community. Instead, a lesser-known trainee lawyer from Petrovgrad, Joseff Sepp Janko, was appointed. Nevertheless, Pančevo remained one of the centers for the mobilization of Nazism among local Germans, who were appointed to all leading positions in the area immediately after the occupation, when a good number of monuments reminiscent of Serbian history or tradition were destroyed. In the first month of the occupation alone, about 400 civilians, mostly Serbs and Jews, were shot or hanged in Banat, without a trial, by random selection of hostages. It is also a curiosity that artist Heinrich Knirr was born in Pančevo, the only portrait painter to whom Hitler personally posed. In one of his offices, Hitler kept Knirr’s portraits of his mother Clara and (oddly) his driver Julius Schreck. It should also be said that the first concentration camp on the territory of Serbia, called Svilara, was formed in Pančevo in June 1941, and that one of the largest execution sites of the war was located on the road to the village of Jabuka, where an estimated 10,000 people were killed.

Camp Svilara in Pančevo; Courtesy of Saša Rakezić

Such a strict regime was, of course, an obstacle to the members of the secret resistance movement, who were often forced to disguise themselves, dye their hair or wear peasant garb when moving around the city, given that most of them were well known to the members of the Volksdeutscher police. By mid-1942, most of the Pančevo’s illegals had been discovered and, after severe torture, killed or sent to other camps, and almost the entire Jewish population had already been wiped from the face of the earth, their property confiscated.

The illegals first gathered in houses, and later in specially built hiding places in the surrounding area, which were more convenient since house gatherings were often broken into, with mutual shooting until the besieged were left without ammunition. In the early days, some of the most common gathering places were vacated bomb shelters, in Cara Dušana Street. It was assumed in advance that some of them would be exposed, so one of the topics in the discussions was the elaboration of a scenario in case of torture. The methods of torture in order to extort confessions about the organization of the movement in the Svilara camp were various – from breaking nails to whipping on the soles while a prisoner lay on his stomach, to putting a hot metal egg under an armpit, to squeezing the head with a special device, and other medieval methods, which were only supplemented by executions in public places. The illegals, on the other hand, organized actions, which represented symbolic acts rather than producing any great damage to the enemy.

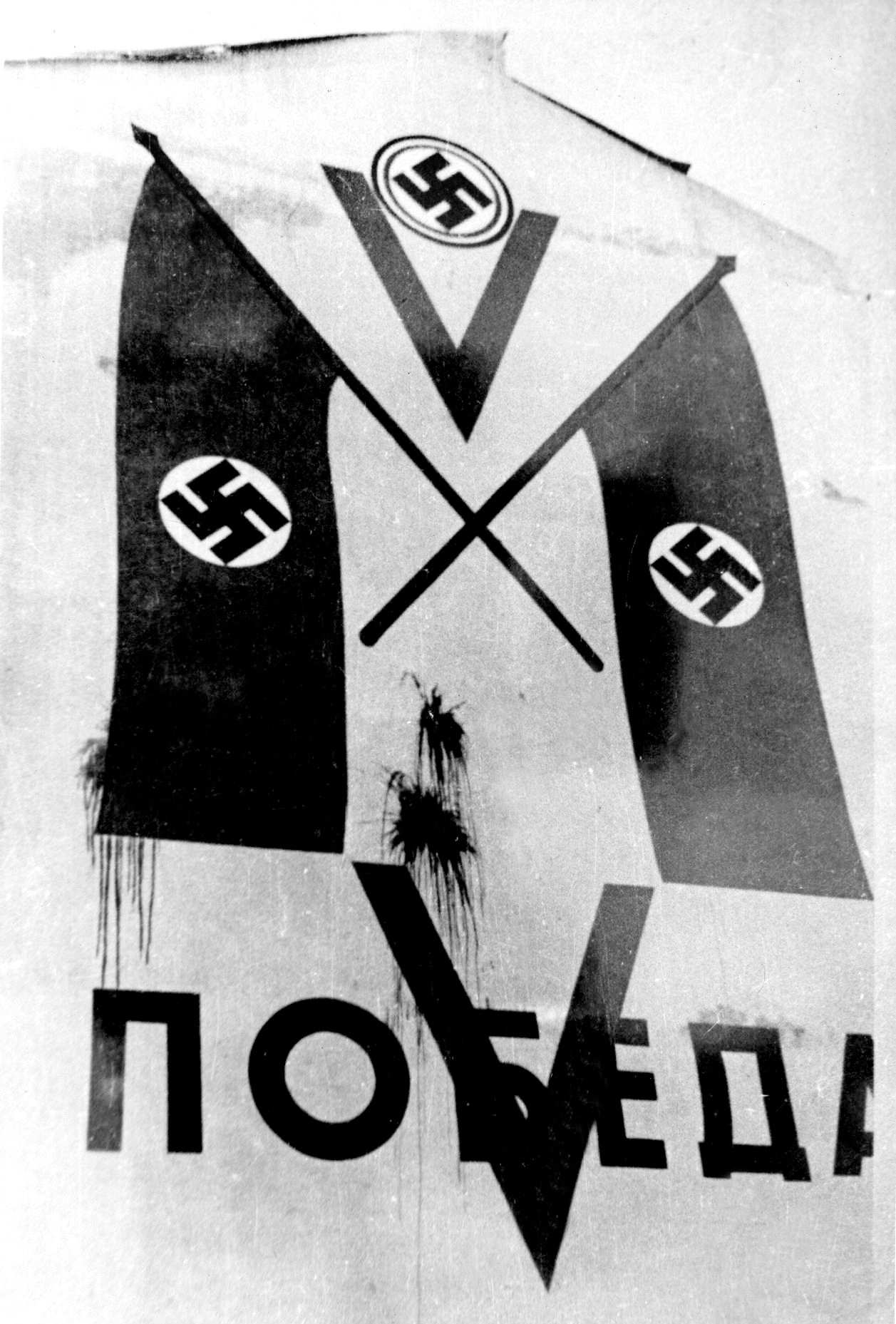

Nazi flags splashed with paint by illegals; Courtesy of Saša Rakezić

Slogans against the Nazis were written, leaflets multiplied in secret printing houses were left at railway stations, and so on. There were also diversions with the aim of disabling military transport, destroying warehouses, and at the same time collecting and hiding weapons and everything that could serve as medical supplies. Most of the illegals were actually high school and university students; some of them were unable to endure torture, after which they betrayed their comrades. There were also Volksdeutscher in the secret resistance movement, and they risked even stricter treatment after the arrest. On the other hand, internationally-oriented, the communists sought to maintain contact with members of all nationalities. In May 1941, Stevica Jovanović, a student of medicine (killed by the Gestapo later in December 1941), organized an informal meeting with a group of employees at the Pančevo’s Glass Factory, where he spoke strongly against the occupation authorities and the need to resist the system. The speech was also attended by the local Germans and afterwards they dispersed, not approving, but also not opposing. It was a very dangerous move, at a time when even for less open statements one could end up in front of a firing squad. However, no one reported it to the police, which meant that, despite the fact that the population of local Germans was able to accept reasonable thinking deep in themselves, the fear was too great.

Concerning the middle of 1942, there is a vacuum in history, to which Petar Pavkov testified in one of his post-war statements – there’s a problem that, after the end of the war, those who were engaged in historiographical recording of events during the first years of resistance in Pančevo no longer had any surviving interlocutors, and it was not possible to reconstruct many of the events. Just after that crisis, Stojan Orelj took advantage of the fact that he wasn’t in the records of the local police and, traveling between Pančevo and Krnjača, he tried to find new associates not among students, but (mostly) among workers and peasants. This created a new secret network, which continued to expand even after Orelj’s sudden death, in the spring of 1944, when he traveled to Belgrade; he did not return. Since this happened during one of the Allied bombings of Belgrade, it was considered that he died under the bombs. (American and British planes bombed oil fields in the Romanian city of Ploiești to disable the Nazis supply of fuel. If they did not manage to unload the entire amount of bombs they were carrying, they could not land, so they threw unused projectiles on Belgrade and other Serbian cities. Since Allied planes had to fly at high altitudes to avoid well-equipped German anti-aircraft defenses, bombs often hit residential areas of the city instead of military targets.) However, despite the premature loss of such a clever figure as Orelj, the efficiency of actions in the area of Pančevo and Krnjača was strengthened by an unusual set of circumstances.

Namely, although the partisan units in Banat appeared very early in the occupation, they could not stay in that area for long. The problem was that the territory was very unsuitable for guerrilla warfare. Banat consists of wide plains, with a large population (often hostile Volksdeutscher population), and with very few wooded areas, so that any movement could be seen from afar, especially if it were groups of armed people. Hiding was only possible when the corn grew, but it was only temporary. There was a partisan detachment stationed in Deliblato Sands, an area unsuited for sustainment of life, vast and arid, which until afforestation in the 19th century resembled a real desert in the middle of Europe. The land is wholly sand, in some places genuine sand dunes. An additional problem was that it was difficult to maintain contact between partisans in the area and several times they were almost completely cut off from other guerrilla groups, even moving across the border into neighboring Romania.

A more favorable territory was on the other side of the Danube, in the Srem area, where the hills and forests of Fruška Gora became a gathering place for partisans. Although they were surrounded by the enemy forces of the Independent State of Croatia and their German Army allies, partisans managed to keep the territory under control in less accessible parts, from where they carried out attacks and diversions. Communication between Banat and Fruška Gora was hampered by the border on the Danube, which was patrolled by German soldiers. One of those who somehow managed to occasionally organize the transfer of people was a picturesque person, Rada Pecinjački, known by the partisan name ‘Šarga’. He was a simple man, living in a hut on the Danube near the Srem town of Belegiš, where he fished and sometimes shepherded the cattle of the peasants in exchange for food and drink. Pecinjački transmitted messages between illegals from Banat and Srem. During 1943, he managed to establish contact with Josef Teisen, the deputy commander of the border guard. According to Petar Pavkov, Teisen had been a member of the German Communist Party since the 1920s, but with the coming of Hitler to power, he was one of those who were forced to conceal their beliefs.

On one occasion, he talked about it to Rada Pecinjački, who lived near the place where the border guards were stationed, and offered him help with transferring partisans and illegals from one side of the Danube to the other. Together with two German guards, Teisen facilitated the removal of the Army from strategic points at predetermined moments, so that boats with illegals or cargo would move to one side or the other. He also provided important information on the movements of German troops throughout the coastal territories, and sometimes personally arranged the guard so that it would be at a sufficient distance at critical moments. The German police came to the conclusion that people were somehow being transferred to partisan centers across the Danube (for example, records show that the population of Pančevo was decreasing), but by the end of the occupation no one could have guessed that it was happening right near where the guard was stationed.

Crossing the Danube to join partisan units; Courtesy of Saša Rakezić

One of the main people who, in addition to maintaining the connection with Pančevo and Belgrade, also worked on transferring people across the Danube, was Petar Pavkov. He was also in charge of providing armed protection in case the activities were discovered, which fortunately did not happen. His associate was a Volksdeutscher from Pančevo, Jovan Rajs. Rajs had several river vessels, as well as a motor boat named Tanja, which he used to transport agricultural products on the Danube. This German anti-fascist left his boats at agreed locations, and there they were taken over by Petar together with his associates, and used to transfer illegals from Belgrade and Pančevo, on the way to join the partisan units in Srem, but also medical equipment, radios and even weapons. The boat Tanja had a secret compartment for materials of special importance – confidential mail or printed material. On a rural estate in Srem, there was a secret printing house, located in a room buried in the ground, and lit by an electric generator. Here, the newspaper Slobodna Vojvodina (Free Vojvodina) was printed, and then distributed in various directions. The warehouse where magazines and books were stored after printing was inside a well – the editor would go down into the well, actually to the storage bunker that was built just above the water’s surface.

Petar Pavkov testified that, on one occasion, according to his records, just one group he led transported over 400 people across the Danube. He also said, almost anecdotally, that the management sent a message that all the space on Fruška Gora was full and that people should rather be directed to some other locations. The fact that some of the illegals, who tried to cross the Danube on their own, were shot by the guards or drowned in the river, spoke of how efficient the organization of these operations was. It is difficult to say whether the whole action would have been possible without the help of people holding positions on the enemy side. Petar Pavkov testified about the fate of Josef Teisen in a statement recorded in 1957. “While the Germans withdrew in 1944, he did not want to go with them, but was left alone in a watchtower where he was found by two boys. I remember, it was when I and a friend came from Srem, we saw two 13- or 14-year-old boys pushing a German officer in front of them and threatening to kill him if he tried to run, and he was trying to explain something to them. I immediately took him with me, and in Besni Fok we gave him a civilian suit so that people would not attack him. He stayed with us until the end of the war. Afterwards, we wrote him a recommendation and he went to East Germany. I heard that he became a councillor in a city there.”

BREAKING IN

Although the transports across the Danube were successful, at the end of the summer of 1944, the tavern where Peter and Spasenija were hiding illegals was raided. Here is how my mother, Milanka (who died in 2007), described it: “I was three years old at the time, but I remember that once in a tavern’s hiding place there was a man to whom my mother brought a jar of sweets. He stroked my hair and offered me the sweets. At that time, someone reported to the Volksdeutscher police that there was a hiding place there (my mother always thought that the denunciation came from someone in the neighborhood) and very quickly the house was surrounded, after which a man who was hiding there was arrested… It is probable that they would have taken my mother, who then had two small children, me and Borivoje, to a camp, but there was also a Volksdeutscher from Krnjača with the police, who lived nearby. That man, whose name I don’t remember, personally guaranteed that my mother had nothing to do with it, although of course that wasn’t true, and that the hideout was built without her knowledge. That’s how he saved our lives. Luckily, dad wasn’t home then, someone had warned him what was going on, so he could escape on time. Later, after the liberation, that Volksdeutscher was captured, along with others who were in the service of the occupying forces. Dad pledged to release him and, after a check determined that he had never killed anyone, the man was indeed set free. I am sorry I don’t know his name and destiny.” When I recounted these events to a cartoonist friend Robert Crumb, he told me that I owed my physical existence to the Germans. That, in fact, is true.

My cousin, Tanja Pavkov, told me how she found out another tragic detail about this event quite by accident. At the end of the 1980s, Tanja worked as a postwoman in Pančevo, and an older woman, to whom she brought mail, began to inquire about her name, what she did, and the like. When she heard the last name, she asked if Petar and Spasenija might be her family. “They are my grandparents,” said Tanja. The woman was delighted, although she was sorry that they were both no longer alive. She said that Petar and Spasenija had saved her family members by hiding them in their tavern during the war. She also said that, after the police entered the tavern in Krnjača, Spasenija, who was pregnant, was severely beaten. After the beating, she miscarried twins. In order to take her to safety, these people moved Spasenija in a horse-drawn carriage somewhere where she could receive rudimentary care. We weren’t able to verify this story, but I don’t know why anyone would invent it.

Here is what my mother told me about the events shortly after the police invaded the house: “The house was under surveillance, at a time when my father was hiding in the swamps. However, at some point he managed to sneak in briefly and take some food, before returning to his hiding place. Vaguely, I remember seeing my dad in some shorts, the suit was probably torn while he was on the run. He had some leather on his feet, wrapped like sandals. That’s all I remember.” After that, Petar most likely crossed the Danube at the appropriate moment and joined the Srem partisans, so he returned to Krnjača only after the end of the war, when he moved to Pančevo with his family.

Petar Pavkov in the partisans (in the middle); Courtesy of Saša Rakezić

A few years ago, I talked to a dear friend, painter and actor, Uroš Đurić. His father, also a painter, Svetislav Đurić, was present during our conversation. I don’t know how the conversation led us to Petar Pavkov, but Svetislav was very surprised when he heard that name.

Svetislav Đurić (right) and Pika Bogić, 1945; Courtesy of Danko Đurić

It turned out that Svetislav’s family, after their house was damaged in the Allied bombing in 1944, moved to Krnjača, where they met Petar and Spasenija, and after the liberation, both families moved to Pančevo, where they live close to each other. As it happened, Uroš and I are already the second generation of people whose families were friends, and we were not aware of that at all, we even grew up in two different cities – Uroš in Belgrade, me in Pančevo. Svetislav told me about Petar’s hiding in the swamps, “You had to muster courage to approach such an inaccessible area at all, let alone to choose it as a hiding place. Not only that Germans didn’t want to go into the area, they were afraid even to stroll around it. Petar was one of the people, quite ordinary people, from the street, who materially enabled the anti-fascist struggle.” Also, I remembered Svetislav’s advice that it is important to stay free from fads and trends in ideology. In fact, Svetislav experienced anti-fascist resistance, but he never agreed that ideology should be the force that would determine the direction of his life. There is another detail – Petar and Spasenija often said that they were disappointed in the people who became the government in post-war Yugoslavia, who went from partisans to high state officials after liberation, and the only person they singled out was Dušan Petrović Šane. Coincidentally, the street where I live, in Pančevo, was named after him. Also, Uroš Đurić grew up in Mutapova 13 in Belgrade, right at the address where Dušan Petrović lived until 1947.

When the war ended, in 1948, there was a split between Stalin and Tito. Yugoslavia chose its own path, unlike other socialist countries. The unity of the Soviet and Yugoslav communists, which seemed so staunch during the war, simply could not function in peacetime. The Yugoslav authorities sent dissidents, especially those who voted for Stalin and not Tito, to an island prison on the Adriatic coast, Goli Otok. In that harsh, uninhabited area, conditions were very difficult, and people who had been persecuted by the fascists a few years before were now persecuted by the communists.

The idea of an island prison is not a new one and it is easy to imagine what it represents – deep isolation as a form of punishment. Places like Spike Island in Ireland or Alcatraz in the United States may have been a model for turning Goli Otok into a prison, used by the Austro-Hungarian authorities for detention of Russian prisoners there during the World War I. And although I’ve never been to Goli Otok, during my stay in San Francisco I had the opportunity to take a good look at the Alcatraz prison, as friends from the Firehouse design team, which mainly dealt with rock posters, made several posters on a friendly basis for the organization that manages the prison (today actually the tourist) complex. As a sign of gratitude, the guards of that space also showed us the parts of the building where access to tourists was not allowed. It is bizarre that I was thinking right here – how did my grandfather get to a similar place? Was he a Stalinist? I have never heard my grandparents mention Stalin at all, although preferences and oppositions easily emerge as a topic of conversation among Serbs. How could they, after all that they suffered during the occupation and their great personal sacrifices, turn against the local victors? According to everything I learned, the people they associated with during the fight and whom they appreciated were anything but a “solid line”. Some were not even members of the Communist Party, and some – like lawyer Veljko Kovačević – were seen as too close to socialist dissidents. Was it a problem that they knew people who were not “faithful” enough? From this distance, when my grandparents are no more, it is difficult to draw conclusions. In 2013, my cousin, Sonja Pavkov, submitted a request for the rehabilitation of Petar Pavkov, which was accepted by the Decision of the High Court in Pančevo.

I can’t say whether my grandparents made a mistake in their political and human assessments. In any case, many of those who considered themselves comrades-in-arms were idealists who were burned in the flames of the struggle, while in their place came those who saw their chance in power establishment. Maybe it’s not so strange, maybe it happens on all meridians, and in different ideological frameworks. The challenges are great, and people can easily become corrupted by privileges. Thus, it was possible for the generation of fighters from the 1940s to be called the “red bourgeoisie” at the student protests in Belgrade in 1968. And in the 1990s, in their later, supposedly wiser years, they had no answers in the face of the forces and people acting as the crude disintegrators of Yugoslavia.

In the end, I want to tell you about the way I think my grandfather said goodbye to my grandmother after his death. Shortly after Petar’s death in 1977, Spasenija told me an unusual story. Over the years, they were together in all those dramatic, beautiful and scary moments of their lives, and now she had to continue on her own. Her thoughts wandered every night, and one time she awoke from sleep and saw something astonishing. Under the chandelier stood Petar, with his arms raised, his gaze fixed on the light bulb. This lasted a few precious moments. When she changed the position of her head, the scene disappeared. It was interesting to me that she said she wasn’t scared to see a ghost, but that she wanted the moment to last for as long as possible. The next day, while she was vacuuming the room, the moment she found herself under the chandelier, the light bulb exploded into tiny pieces that fell onto her hair.

The Origins: The Background for Understanding the Museum of Yugoslavia

Creation of a European type of museum was affected by a number of practices and concepts of collecting, storing and usage of items.

New Mappings of Europe

Museum Laboratory

Starting from the Museum collection as the main source for researching social phenomena and historical moments important for understanding the experience of life in Yugoslavia, the exhibition examines the Yugoslav heritage and the institution of the Museum