On the Occasion of the Centenary of the Founding of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia

The importance of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in the creation and life of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia is indisputable: almost half a century it was the only party in the country, why is why it is largely considered responsible for all the successes and failures of the country. However, the role of CPY in the life of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia is usually neglected.

Established only five months after the creation of the first Yugoslav state, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia was one of the first political parties with Yugoslav platform and it stayed the only one with such a direction until the end. It was the first political party to carry the designation of “Yugoslav” in its name. While the time of the founding of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia almost coincides with the moment of the first Yugoslavia’s formation, its breakdown in 1990 was the introduction to the disintegration of the second Yugoslavia, which was created by the party itself. The Yugoslav idea, realized in the formation of the Yugoslav state, and socialist ideas represented by the CPY, were actually true alternatives. The former was the alternative to conflicting nationalisms of small nations, and the latter was the alternative to the universal injustice of the capitalist system. In retrospect, it is clear why these alternatives, as well as any form of memories of them, have been so unwanted in the dominant right-wing political milieus and the regime of liberal capitalism, which flourishes on the territory of the former Yugoslavia.

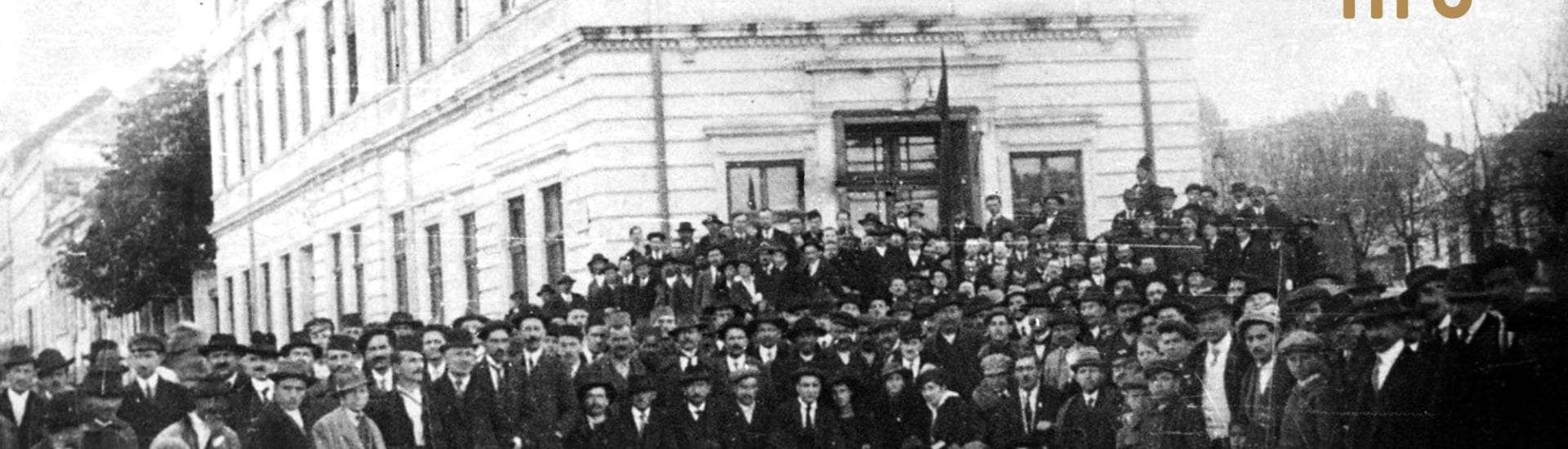

In April 1919, the Congress of the unification of social-democratic parties and organizations in the area of the newly created Kingdom of Yugoslavia was held in Belgrade. During the Congress, 432 delegates represented about 130,000 members of the organized labor movement from all over the country. They decided to form the Socialist Workers’ Party of Yugoslavia (communists). Under the impact of the recent developments in Russia, the congress participants pleaded for a revolutionary way of political struggle and the dictatorship of the proletariat, and for joining the Communist International. Filip Filipović and Živko Topalović were chosen as a president and a secretary. The entire Serbian Social Democratic Party, the Social Democratic Party of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Social Democratic Party of Dalmatia, and partly the membership of the Social Democratic Party of Croatia and the Social Democratic Party of Slovenia all entered the new party. A more widely recognizable name – the Communist Party of Yugoslavia – as well its program, the party received at the Second Congress, held a year after in Vukovar. In this way, the CPY, which lived about as long as the state where it was created and whose destiny it shaped, was formed. Development of this party was contradictory and complex, as was the life of the country in which it existed and which it later managed. That development led the party from being the only true alternative to the existing political and social order in the Kingdom, to disregarding the alternatives to the order that the party itself established during the Socialist Yugoslavia.

The establishment of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia relied on the tradition of the labor movement, which has evolved since the last quarter of the 19th century in these countries, but also on the revolutionary flight originated by the victory of the October Revolution. Under the impression of revolutionary situation across Europe, but also on the wave of the unresolved national question in the new Kingdom, on the elections for the Constituent Assembly in 1920, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia won an impressive number of votes, and became the third largest party in the country. The distribution of election results showed the duality of support it enjoyed. While, on the one hand, the great support in the cities could be explained by the numerous working class and the extremely difficult conditions in which people lived (Belgrade and Zagreb even got communist municipalities, but they were not approved by the royal government), a significant number of votes won in Macedonia and Montenegro testified primarily about national dissatisfaction in these provinces. Also, because of the strength of the program they represented, the communists were the first against who all the power of the government turned, and this case clearly showed the undemocratic nature of the system, which defended itself by limiting and then completely prohibiting any communist activity. There was a period of illegal operation, when the party was placed on the margins of political life, wandering in fractions’ fight, exposed to the crucial impact of the Comintern, while its very existence was doubtful. However, at the beginning of the Second World War, the party emerged from the underground and stood at the head of the armed uprising that would eventually lead it to power.

During the Socialist Yugoslavia, the panegyric showing of the party’s past dominated, including the period of underground operation, with the omission of all people who later offended the party. Even after the fall of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, the history of the labor movement in the interwar period has not been critically examined, or, to put it more accurately, it has been examined only hyper-critically. The topics that were forbidden in the time of socialism were updated, like Bolshevization of the CPY, its cooperation with extreme nationalist movements, acceptance of the platform on the Yugoslav framework break-up in the period from 1924 to 1935, but they were now interpreted in such a manner that little of essential events, processes, and phenomena could be understood. One conclusion has imposed itself from all of this. Research and presentation of the history of the labor movement and the Communist Party must be approached using instruments of social history. Only with understanding and appreciation of the wider historical and social context, bearing in mind the events in other parts of Europe, can we understand the key processes, such as the support that the movement enjoyed for a period of time, the role of the prohibition, persecution and “white terror” in the reducing of its members and strengthening the core of the movement, but also in its final abandonment of the legal ways of fighting and democratic system of government. Presenting the history of the labor movement and the illegal activities of the party without this approach is mainly confined to the account of covert activities, games of intelligence services, false identities and terrorism, and it stays at the level of political thriller, a bad one at that.

A more complete consideration of the past leads to its understanding, and thus to understanding the present, on which such a past has left its mark. It has to be borne in mind that both the state and the political and social system in which we used to live, has disappeared from the map of Europe. Nevertheless, they remained in the form of “mental maps”, much deeper than those drawn by politics and wars. As much as possible, we need to think and judge about them based on products of science, free from the pressure of national politics and emotions.

The Origins: The Background for Understanding the Museum of Yugoslavia

Creation of a European type of museum was affected by a number of practices and concepts of collecting, storing and usage of items.

New Mappings of Europe

Museum Laboratory

Starting from the Museum collection as the main source for researching social phenomena and historical moments important for understanding the experience of life in Yugoslavia, the exhibition examines the Yugoslav heritage and the institution of the Museum